"190e30-Now with COSWORTH" (190e30)

"190e30-Now with COSWORTH" (190e30)

03/26/2015 at 15:01 • Filed to: None

0

0

0

0

"190e30-Now with COSWORTH" (190e30)

"190e30-Now with COSWORTH" (190e30)

03/26/2015 at 15:01 • Filed to: None |  0 0

|  0 0 |

Disclaimer: This was originally written for a safe driving essay for a college scholarship, but upon finishing and learning I was 1700 words over the word limit, I restarted. Considering the amount of work I put into it, I figured I'd toss it up here, since at least one person may enjoy it. As a result of this, much of the article is in layman's terms, and the basics of track cars that we all know and love are way over-simplified.

On January 25th, 2014, in Daytona Beach, Florida, participants toed the line in over 50 high-performance racecars at the annual running of the Rolex 24.

The safety standards in this event can be considered the "best of the best;" strict safety qualifications require a roll cage to prevent deformation of the vehicle in the event of a crash, crumple zones to dissipate energy in high-speed collisions, structurally-reinforced helmets to protect drivers, HANS devices to hold the drivers' necks and prevent damage from rapid deceleration, and some of the most highly-trained safety and medical staff in the country. This needs to be the safest race in the world; with cars touching speeds in excess of 150 miles per hour every lap while their drivers, sleep deprived, hard-focused, and under pressure, aim to squeeze every last drop of performance out of their iron steed, failure from either the mechanical or living beast are inevitable at some point.

On that day in January, it didn't take 24 hours. It didn't even take 12.

Memo Gidley, driver of the number 99 Chevrolet Prototype car was following closely behind a slower car down the back straight-away, angling for a pass. The target, a green and yellow Ferrari racing in a lower class, raced down the asphalt at close to 100 miles per hour, the two a seemingly inseparable train of speed, with only feet between each other.

Roughly an eight-mile ahead of both drivers, obscured by a swarm of other competitors in slower cars from different classes, sat Matteo Malucelli, in his number 23 Ferrari 458.Malucelli had been running an impressive race. It wasn't until the middle of Lap 94 that the Ferrari decided to give up on him, and he was left, stranded in a wounded car, rolling down the back straight-away at about twenty miles per hour with the blinding sunset of Daytona Beach pouring through his windshield.

Behind, in Gidley's battle, the two cars crested speeds of over 100, weaving around slower cars at an incredible rate. As the green Ferrari passed a backmarker, Malucelli sat only feet ahead in the broken Ferrari, nearly stationary in the middle of the racetrack. The green Ferrari swerved violently, missing the Ferrari by inches and pitching itself into the grass of the track before eventually wandering back onto the course.

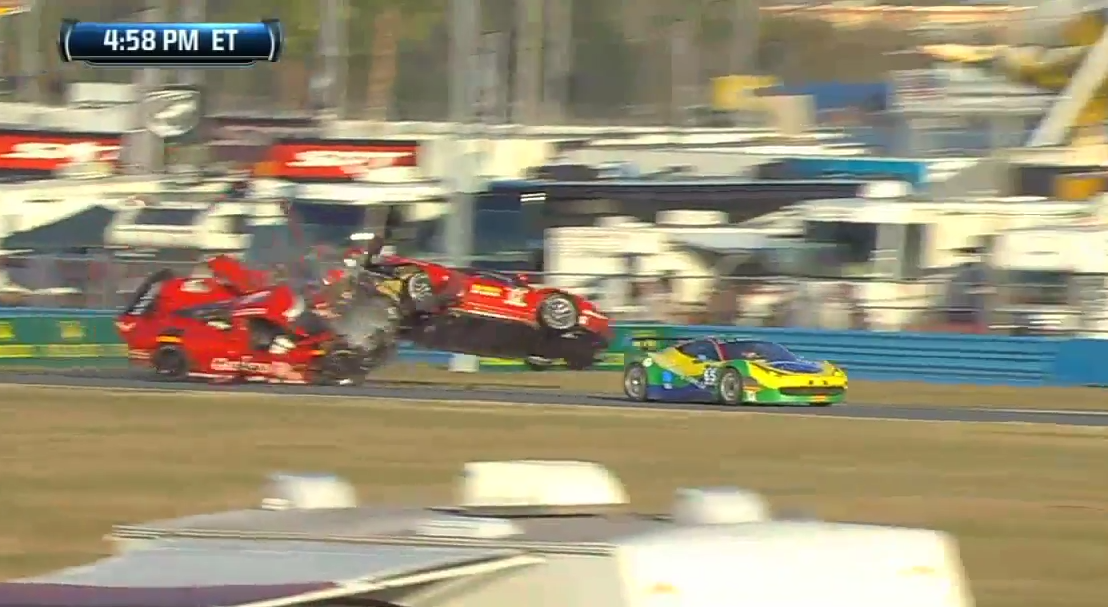

Gidley, who had been nearly touching the rear-end of the green car and was blinded by the setting sun, never saw Malucelli. At over 100 miles per hour, as the green 458 moved, Gidley never had the chance to respond to the Ferrari sitting stationary only inches ahead of his car. He plowed into the back of the parked racecar, launching both cars into the air and slinging metal and fire across the track.

Both drivers were lucky. Malucelli's Ferrari was mid-engined, meaning the engine was placed behind the driver and towards the rear of the car, absorbing much of the impact from the violent collision. He only had to spend a single night in the hospital with minor injuries.

Gidley, whose vehicle was also mid-engined (meaning there was nothing to dissipate energy in his car), was even luckier. Thanks for the over-engineering of his Chevrolet prototype to make driving at such ludicrous speeds reasonably safe, he only needed a handful of back, arm, and leg surgeries to repair his broken bones.

Watching the accident occur both live-in-person and live on TV, spectators thought they had just watched the the death of the two drivers. And realistically, they would have, had the drivers not been wearing the most expensive and well-designed crash-safety gear money can buy, and had they not been driving cars designed to flip end over end at highway speeds without simply becoming a piece of sheetmetal like any other vehicle would.

Gidley was subjected to a handful of strange circumstances, a cocktail of chaos that caused the crash to occur. Several other cars obscuring the vision of the vehicle in front of him. Following closely behind the aforementioned "blind" driver. A slow-moving car in the middle of the racetrack. All of these strange circumstances led to Gidley's near-death collision, and his car and equipment saved his life as they were intended to.

I continued to watch the rest of the race, but there was a nagging question in the back of my mind. Yes, Gidley was traveling at a great deal of speed, and yes, it appeared to have been nearly impossible to avoid the collision. But as a normal teen driver, what if I was faced with that perfect cocktail of chaos, on a smaller, slower scale? A car slamming on it's brakes in an effort to escape down the freeway exit it's about to pass, like we have all witnessed before. A piece of truck tire sitting in the middle of the highway, invisible until the car in front of me swerves around it. Gidley had no chance of avoiding the Ferrari at 100, and his safety equipment saved him from death. I didn't have any rollcage, or a HANS device, or a harness, or a deforming car designed to crash. If I was faced with that same perfect whirlwind of disaster, would I even have a chance of survival?

That's a big shunt.

I began to research.

I found that the US National Library of Medicine performed a study in 2006, comparing the reaction times of "eight elite racing drivers" to "10 physically-active controls," who were matched in both their age and their weight. The two test groups were required to respond to a series of visual and audio cues, using both their hands and feet. In this study, the testing showed that "The reaction time of the racing drivers was significantly faster than the controls."

So that answered one question. No, I would not react even remotely as fast as the professionals, Gidley and the driver of the green Ferrari, had. At first this didn't bother me, as I realized I would likely never be faced with a car materializing out of nowhere only a few feet in front of me whilst doing such a high rate of speed. But then I began to wonder again, just how much time would a normal kid like me have to take evasive action? I went back to work.

At the time, I had managed to buy a fairly impressive performance car, a 1998 BMW M3, under my own funding. After some brief googling, I learned that according to numbers released by BMW of my car at the time of reveal, my car would stop from 60 miles per hour in 112 feet. Picturing this myself, I felt fairly confident; From 60 to zero, this was far shorter than I had anticipated. Surely, I would be safe. Right?

I had trouble finding information regarding the stopping distance of Gidley's car, but what I did learn did not provide any comfort. A BMW M3 GT2, a competitor of Malucelli's in the slower car class, was reviewed in a road test by Car and Driver. "...but from 120 mph to 0, the M3 GT's performance is roughly equal to the [Corvette ZR1], despite not having the benefit of anti-lock brakes." Some more googling revealed that the Corvette, according to Jalopnik.com, would do 60-0 in only 94 feet. That's right- The M3 GT2, a car slower and less sophisticated than the one Gidley was driving, would do 120-0 in only 94 feet. 18 feet shorter than my car would from half of the speed, when traveling on the highway.

I had learned that I would not be able to react fast enough in a close, high-pressure, bizarre situation, and even if by some miracle I did, I would not be able to stop in time due to the limitations of my own vehicle. There was still one big elephant in the room though, and that was the cause of the accident; visibility.

Video footage of the accident showed about a second between the green car moving and Gidley's impact. Just before the impact, footage shows Gidley's brake lights clearly flickering on, his final effort to get the car stopped as much as possible prior to the inevitable impact. I timed the gap from when Gidley, the professional driver, first saw the Ferrari in front of him to when his actual preventative response took place, the illumination of his brake lights. Over three trials, in an effort to eliminate my own physical errors, I found an average reaction time of .38 seconds from Gidley. And upon researching, I learned that the average Americans are reported as taking an average of anywhere from .7 to 3 seconds to react behind the wheel, according to an estimate by copradar.com over data gathered via a controlled study in 2000.

Gidley reacts almost instantly to the unseen hazard at 2:09.

I was starting to come to the conclusion that in the event of a stationary car, obscured vision, and high travel speeds, death would be almost inescapable for the average person in an average car. And then I remembered something from driver's education.

I had been told in my schooling to follow the "3-second rule." Pick a stationary object on the side of the road, such as a telephone pole or a sign, and wait for the car in front of you to drive past. Begin counting, and when you pass the targeted item, stop. A gap of three seconds would be considered "safe following distance."

After doing some math, I learned that if I had been traveling at 60 in my own car whilst observing the three-second rule, I would stop in only 88 feet, leaving me 6 feet short of the imaginary obstruction assuming the vehicle was equally as invisible as the Ferrari had been to Gidley.

So, the moral of the story? Pay attention, and maintain a safe following distance. You never know what might be waiting around the next corner or hidden in front of the vehicle in front of you.